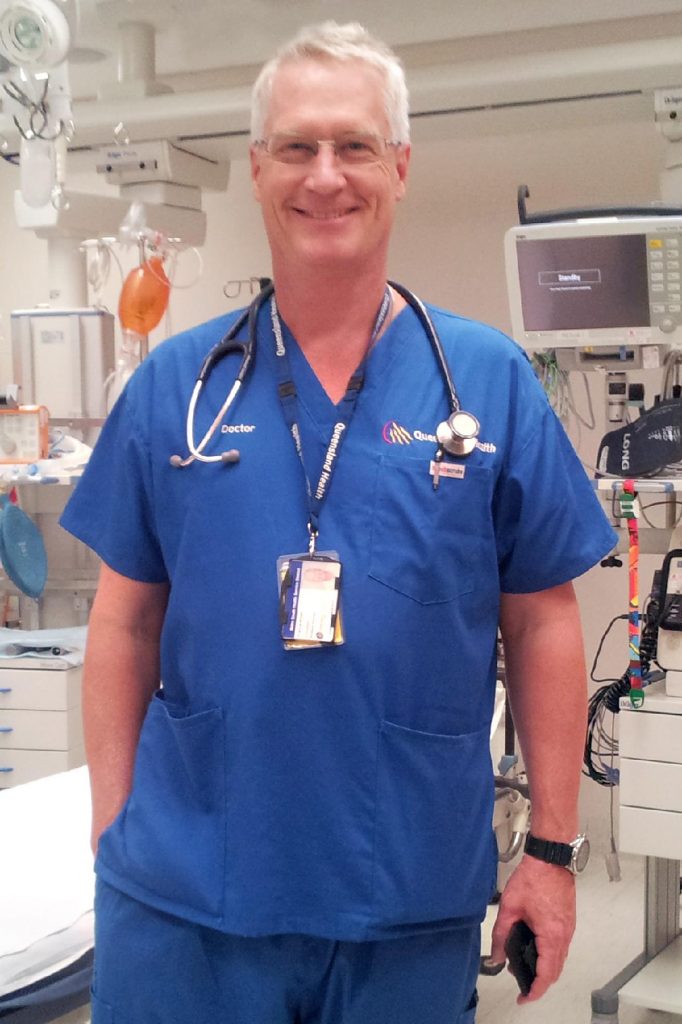

The Medicine section of DDU relates my experiences and observations while working as a front-line emergency doc in the Australian public-healthcare system for over six years. With the last 1 1/2 years being a full time fly-in locums EM doc. In all, I worked in ten different ED’s, in four different Aussie state systems, so I’ve seen a lot, maybe more than most of my Aussie colleagues!

The Medicine section of DDU relates my experiences and observations while working as a front-line emergency doc in the Australian public-healthcare system for over six years. With the last 1 1/2 years being a full time fly-in locums EM doc. In all, I worked in ten different ED’s, in four different Aussie state systems, so I’ve seen a lot, maybe more than most of my Aussie colleagues!

I’ve also held ED directorships in both AU and USA and numerous medical staff committee roles in the USA, including a stint as medical staff president at a local community hospital.

At this point in my career, I’m most interested in using these experiences to help inform the current debate in the USA around re-designing our public healhcare system, from a clinical perspective. My intent is to inform readers; giving them the good, the bad and the dysfunctional in both systems. One thing I’ve learned is that there’s no perfect healthcare system! It’s really a matter of balancing patient needs and community expectations with available resources and realistic cost: benefit considerations. While I have my own opinions for moving us forward in the USA, my main goal is to inform and present options as I’ve experienced them, first-hand. Good intentions don’t necessarily translate into good outcomes…

As I delve more deeply into the policy side of medicine, I hope to be updating this section fairly regularly. Please return occasionally, and kindly leave a message as to how I’m doing. This is all a new venture for me!

For starters, attached below is the main Healthcare chapter from my just published “Doc Down Under” book for FREE! While comparative healthcare delivery is a core theme of the DDU book, it’s by no means it’s sole purpose. So, I’ve decided to keep that component of the book to a minimum, in the interest of providing a more satisfying read to non-medical administrative policy wonks. Still, I’d like to share the ideas I’ve sketched out below with as wide an audience as possible, but felt the topic is better addressed outside the DDU book. Please feel free to copy this article and share it around. If you find something of value or interest in here, perhaps you’ll be moved to leave a comment, or even purchase the DDU book, available now available on Kindle/ Amazon. And it’s FREE if you have Kindle Unlimited. Thanks for your interest, Francis Nolan, MD, FACEM, FACEP (aka Doc Down Under ! ).

Healthcare – Comparative Healthcare System Economics 101

Having now worked in the Australian Public hospital system for over six years, and per diem on the Private side for one, as well as the US system for over twenty-five years, including three years full-time in the US Public Health Service/ Indian Health Service, I feel I’ve gained some hard-earned perspective. Australia’s system is, to me, clearly better; the end… mostly…

In fact, as with most complex issues, the on-the-ground reality is far more nuanced than a few handy sound bites can accurately capture; and attempting to sell a complex concept with a few simple, broad-brushed strokes that the public might get behind is ultimately self-defeating. But healthcare is important; it matters, or should matter, to all of us. It has to work at the patient and family bedside experience level and be cost-sustainable ongoing. Though it’s well beyond the scope of this (supposedly lighthearted) book to dissect fully, my unique experiences and perspective might help to illuminate some issues, and I’ve taken the liberty to provide some broad suggestions for my American readers to consider as we stumble forward in this area of vital interest to all citizens worldwide. But, again, these are only my opinions and insights here, not gospel truth.

As we embark, a few disclaimers. I’ve been a front-line ED clinician for over twenty-five years, as well as an assistant or full ED Director for much of that time. But I’m not a politician or a healthcare economist (thankfully). My opinions are rooted in my own personal experiences and observations, as well as extensive discussion with fellow Medical, Administrative and Nursing professionals. I’m also a residency-trained, board-certified Fellow in Emergency Medicine in both the USA (FACEP) and Australia (FACEM). So, my perspective may be somewhat focused, but it’s very real-life; extensively clinical and not theoretical. I happily acknowledge my imperfect understanding of these vastly complicated medical delivery, management, IT and reimbursement systems. In reality, no one truly understands them in total; or the ultimate net effect of tweaking any components of them. Error, miscalculation and unanticipated consequences abound; as clearly witnessed by the costly Clinton and Obamacare collapse fiascoes in the USA most recently.

Good intentions, and well-meaning initiatives for better, more cost-effective outcomes don’t necessarily translate into clinical reality. Policy wonks, politicians and regulators appear to most clinicians I interact with to be somewhat arrogant and out of touch with front-line clinical staff’s concerns and daily realities. Who made these people the “experts” anyway – folks who’ve never actually stood at the bedside and cared for a single patient in their entire careers? But they are so full of bright ideas! Good luck with accepting and implementing their insights without hearty doses of skepticism. And they seem to be able to somehow walk away from their messy outcomes unscathed professionally; perhaps to work their magical thinking elsewhere in the system. We clinical folk cynically refer to this as “Failing Upwards”, to new areas of expertise and responsibility…Gulp…And in truth, these strange folk exist in both the USA and Australian systems. And in ever larger numbers. Not a good omen for the future.

But that doesn’t work for me and my colleagues. We can’t simply walk away from our, or their, messes; we live here. And so do our patients. Dishonesty and obfuscation run rampant, and most politicians, being essentially cowardly if votes are at risk, will allow inertia to run it’s fateful course and not actively engage in advocating for, or leading, meaningful change; if speaking reality is at all likely to be painful to some demanding constituency or other. Oh, but it will be, I promise.

That said, in my experience, the Aussie system is the best I’ve encountered, and with a few tweaks, is likely one of the the most sustainable, as well as efficient, comprehensive and cost-effective systems out there. It was recently so rated by The Commonwealth Fund in a study of eleven advanced western democracies, across a broad range of metrics. Along with the UK, AU was rated the most cost-effective healthcare delivery system worldwide; when measuring health outcomes vs dollars spent per capita. The US, unfortunately, came in dead last by a wide margin, despite spending more than double the group average, as a percentage of GDP. We are now rapidly approaching 17% of total GDP. Something’s broken here folks…and adding more layers of non-patient care expenditures and regulations isn’t going to fix it; that’s pretty clear to me and my peers.

Here are a few surprising factoids to get us started:

The Aussie Public system depends heavily on a parallel Private system to off-load demand. Around 40% of Aussies have at least partial Private cover. However this percentage is dwindling as insurance costs in the Private sector accelerate.

Every wage-earner pays into the Public system and has access to it. Around 2.5 % of salary base-pay is captured via payroll taxes for the Public (Medicare) system. Everyone, including my family once we attained Permanent Residency status, has a Medicare card. There are some interstate variances, but in Queensland, Medicare covers all costs of Emergency Ambulance services (also State run), Emergency Department and Trauma/ ICU/ catastrophic care.

In Australia, this Public Medicare means of covering extreme emergency (unforeseeable) costs then allows the extensive Private system to extend additional Private insurance cover at bargain prices (by US standards). To sweeten the incentives, high-earners are tax-advantaged to carry Private cover in various ways. For example, as of 2018, let’s say you are a high-earner making $ 250- 400K/ yr. You will pay 2.5% base pay Medicare levy from your payroll taxes, or ~ $ 6,250-10K, for Medicare cover for your entire family. If income is greater than $250K, and you choose not to carry Private cover, you will incur an additional Medicare surcharge levy of 1%, or ~ $ 2.5K- 4K; for a total of ~ $ 7.5-14K, for fairly comprehensive family care without high deductibles and minimal co-pays, delivered solely within the Public system. Lower earners don’t incur the 1% surcharge and charges are capped at 2.5% of their income. But, importantly, all wage-earners contribute something to the Medicare system. So, a family making $80k/ yr, would only incur a Medicare levy of $2000 and remain fully within the very capable Public system. They’d have little incentive to add Private insurance cover, but could do so if desired.

If instead, you’re the lucky duck making $400K, and elect to take the Private cover, you can obtain a pretty comprehensive Private family package, with minimal deductibles for, in my case in 2017 (family of seven) ~$360/ month or $4320/ year; for a rough total of around $14 K/ year. There may be additional co-pays for highly-specialized services, which are constantly adjusting, but nothing approaching the US charges. Essentially, as a high earner, your insurance costs for additional Private cover are similar to if you had stayed in the Public system and were hit with the 1% surcharge levy. Make sense? And Private cover in Australia is, by US standards, pretty amazing; including fully Private hospitals/ rooms, surgeons, advanced care with almost no delays or waiting times.

Major trauma and complex ICU/ critical care is generally centralized and delivered in the Public system, where the majority of the training Fellows and Registrars (Medical and Surgical Residents) work primarily. This is somewhat the reverse of the US system, which depends heavily on many excellent, world-class Private, not-for-profit healthcare networks; eg the Mayo, Cleveland, Geisinger, Leahy, and Carillion Clinics etc; and has a skeletal truly Public hospital system. I trained at one, Boston Medical Center, and am well aware of the risks for inefficiencies and entrenched bureaucracy that the old school Public hospitals can entail. I’m just pointing out how differently the two systems have evolved since WW2 and what that might mean when visualizing any future hybrid system developing in the US.

By necessity, any US-styled, basic single-payer system would need to leverage the existing Private not-for-profit networks, which are world leaders in cost (if not charge) efficiency and cutting-edge care. It would ideally involve some form of basic Medicare/ Medicaid for all, paid via payroll levies, on the reimbursement side, and have a parallel Private Insurance/ Hospital track for those willing to pay extra, similar to AU. In fact, the current not-for-profit systems in the US are already heavily subsidized by Federal and State funding, especially Medicare reimbursements, and could not exist without them; thus we already have a hybrid system of sorts in place.

One little-discussed area of non-sustainable healthcare costs that needs to be addressed as a priority is the extreme overcompensation of US healthcare executives and senior Administrative staff; a trend that represents essentially asset-stripping of their respective corporations by insiders, and enabled by their Boards of Directors, in my opinion. A 2017 Equilar 200 Survey of the top CEO salaries in the USA identified that 17 of the top 100 CEO salaries were awarded in the Healthcare and Pharmaceutical industries. Ranging from #6, at $26.17 million, down to #99 at a paltry $ 3.65 million, for a single year’s effort! What justification can these CEOs and their Boards provide to add such egregious costs to the delivery of such a vital service to the American public? Especially in an environment where over thirty million of our fellow citizens remain without basic healthcare insurance coverage! It’s simply unconscionable to me as a practicing, front-line physician. None of my colleagues make anywhere near a fraction of these payouts, regardless of their specialty training; and we treat the patients and deliver the actual healthcare.

Recent corporate history in the US Financial, Automotive and Airline industries has shown repeatedly, that these corporate boards are in general, unable or unwilling to control such blatant Executive parasitism. Simply compare the average CEO compensation in the USA, across industries, with the rest of the developed world. We are a clear outlier here, with little justification. It’s fine with me, if the shareholders are willing to bear these additional costs; but only in a truly Private, non-vital sector of the economy. Not healthcare. Leaders must lead by their example.

While I’m certainly no Socialist, may I propose a simple, common-sense solution here? By Presidential Executive Order, declare a healthcare cost and insurance coverage national emergency. Any healthcare or hospital-based corporation that receives or contracts for public State/ Federal healthcare funding or reimbursement (virtually all of them), must rapidly transition to an annual cap on total individual executive salaries and compensation at ~$2 million ( $1m ?) in total compensation or become ineligible to bid for, or negotiate with, any State/ Federal healthcare funding entity. Windfall capital gains and/ or stock options above this cap must further be rolled back into the parent organizations and used to lower patient charges for products and services provided; but not to provide for additional dividend payouts or stock buybacks. If these corporate officers don’t feel they can sustain their lifestyles on $1- 2m annually, let them resign and work in a non-critical industry. I’m certain that many willing and able physician executives will be eager to fill their shoes, and good riddance to them. Why has this issue never had a widespread public discussion? You can probably figure it out.

Not to suddenly turn DDU totally wonk-ish on you, but according to the OECD 2015 Heath Statistics report (using 2013 data) Publically-funded healthcare spending in the US was already 48% of all healthcare expenditures in 2013, compared with 68% for AU and 80% in NZ. Surprisingly, the same OECD data revealed that, in terms of out of pocket HC spending as a % of total HC spending, the US, at 12%, was actually 3rd lowest of the OECD countries, vs 20% in AU and 13% in NZ! Only the UK (10%) and France (7%) were lower. Thus, governments , at all levels in the US, are already heavily involved in healthcare delivery at a financial and even operational level.

Finally, per recent WHO data, per capita Government healthcare (Public) expenditure in the US is actually 4th highest in the world, and surprisingly, more than both AU (#16) and NZ (#17), likely a marker for US healthcare system cost inefficiencies and higher administrative costs. The administrative costs of managing the complex and fragmented US system are largely hidden, but simply astronomical. A recent NY Times article, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/16/upshot/costs-health-care-us.html sites a NEJM study that projects overall Administrative spending in the US at an astonishing 31% of total healthcare spending! This, compared with 16.8% in Canada, is roughly double, using the same 1999 data. That’s one of every three US healthcare dollars spent non-clinically! A Commonwealth Fund report, using data from 2010-11, placed the US in first place yet again among eight western economies, spending 25.3% of healthcare funds on Administration, with the next closest being the Netherlands, at 19.8%. Canada and Scotland were lowest at 12%, with no discernible link between higher Administrative costs and better healthcare outcomes.

https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/journal-article/2014/sep/comparison-hospital-administrative-costs-eight-nations-us.

Unfortunately, for complex societal reasons, all this additional expense is borne with less than average OECD patient outcomes overall. And all these costs are eventually charged to the patients, taxpayers and insurance policy holders in the form of higher charges, and increasingly un-affordable insurance premiums. Healthcare Administration in the US is a major area of cost inefficiency that requires much more public awareness and transparency; leading to aggressive cost containment and rigorous demands for demonstrable benefit and better “bang for the buck.”. And please understand, most of these various non-clinical initiatives and programs, however well-intentioned, are generally non-reimbursed to the hospitals, and generate zero revenue. Thus, they are all cost drivers that add enormously to the final, grossly-inflated patient charges.

To my understanding, the primary issues in the USA are an insurance coverage and affordability crisis (accessibility) rather than a structural deficit of dysfunctional or decaying infrastructure – far from it, the USA not-for profit networks have world leading physical campuses and facilities. Some might even argue, overbuilt for purpose at such high cost. But, at least such systemic accessibility problems are potentially much easier and less costly to correct. Thus, hope exists if we have the courage to proceed.

The other severe drawback to how the US healthcare system evolved post-WW2 is that for many, healthcare coverage has been tied to employment. So, if you lose your job, you also lose your health insurance; a real double whammy that doesn’t exist in Australia. I’ve read recently that over half of all US personal bankruptcy filings have unanticipated medical costs as a major contributing factor.

This, to me, is the greatest benefit of the Australian system; the peace of mind in knowing you are covered fully for any serious conditions without possibility of cancellation or dramatic rate increases. In our six years in Australia, we’ve been on a real roll; depending on the Public/ Private hybrid system for two pediatric appendectomies, an ovarian vein oblation, a hydrocele repair, a basal cell skin cancer MOHS surgery and numerous outpatient tests, ultrasounds etc. The care was always top-notch, friendly, caring, efficient. At the cost, I can’t think of a better country to get sick in!

Healthcare costs in Australia are still surprisingly in check, at approximately 6-8% of GDP, around the median for western democracies; and health outcomes metrics, like lifespan, childhood health etc are among the best in the world. The USA, in contrast, spends roughly 17% of GDP on healthcare, more than double the OECD average, and scores only in the low-middle of the pack in terms of overall outcomes.

But alas, all is not perfect in (near) paradise…The Aussie public system does have its inevitable drawbacks and limitations.

While no-one is denied care, Public budget realities dictate that not everybody gets everything they want. Surgical care and procedure scheduling is done on an urgency-of-need basis. Hospitals are closely tracked and graded on their performance, say for surgical removal of high grade tumors, a Category (Cat) 1 condition. These are routinely completed 100% in 30 days, or whatever the particular standard is for each specific condition. Excellent metrics across the board…really, world-class.

However, if you are, let’s say, an obese 55 year old with a chronically sore left hip due to moderate osteoarthritis, perhaps a Cat 4 condition, you will be placed on a waiting list, along with all the other Cat 4 hip patients. These will be delayed as higher Category conditions are absorbed onto the waiting lists, and you might wait a very long time indeed before you get your semi-elective hip surgery; perhaps years and years, and possibly never. With Private cover, and the typically excessive Private operating theater capacity that exists, assuming a clear indication of need, you could have the same surgery within thirty days. This same model is extant across all disciplines. And highly in-demand Specialist consultation, ie Rheumatology, Endocrinology or Dermatology are in pretty short supply in the Public system; while relatively plentiful in the Private. But, really, is that so bad or unfair in a Publicly-funded system? How else could you run things; first-come-first-served regardless of severity? I don’t think that would work out very well.

These realities then evolve into a philosophical discussion re: limits of care and cost-effectiveness of a system measured on a population, rather than an individual (personal), basis. And at the end of the day, I believe this is one of the greatest disservices politicians and policy makers perpetrate on the public; that we can somehow do “everything for everybody”, and that “nobody should wait or suffer”, and that healthcare should somehow be “free for all…” Like our current free-for-all? The practice of deficit spending to further extend healthcare cover, avoids an unpleasant reality; that all systems have their limitations and must eventually pay their own way on-going, to remain sustainable. And worst of all, is passing the bloated bill on to future generations (via a debt burden) to fund our current “needs”. As a physician and citizen, I find this model, which has become rampant in the USA and most western democracies, to be highly repugnant and unethical. At least Australian society still has the courage to have an honest discussion about what is affordable on an on-going basis, and tries to adhere to its budget. Though, here too, there’s increasing push-back from various patient’s rights advocacy groups and invested stakeholders. I liken “free” healthcare to baking free pies. If you set up a system of unlimited “free” pies for any and all, you will simply never be able to bake enough pies. Demand will be insatiable, and gluttony become rampant. The earliest at the table will eat their fill, and more… Everywhere today, it seems, people want their “free” pie, and more, and more of it.

The USA certainly needs a similarly honest, mature and open discussion ongoing, about debt-free, healthcare funding realities. But seems to lack the courageous leadership to do so; thus the “free “ pie fantasies, and deficits, continue to grow.

And finally, to my mind, much devolves down to another simple philosophical question: “What does any society truly owe to each of its individual members, and what is each person’s expected contribution vs withdrawal from that society?” Obviously, for such a system to be sustainable without deficit spending, at least as many must be contributing as are withdrawing from the pool; that’s the actuarial basis for all insurance policies. My observation is that any such Public system is guaranteed to fail unless every capable, adult member has “skin in the game.” and self-controls their demands on it. “Skin in the game”, via mandatory co-pays, public-benefit payment reductions and utilization caps could change the game completely.

Another misconception that Americans will need to take into account, is that physicians, nurses and allied health workers would somehow make dramatically less in a Public-funded system. Not in Australia, where the pay is equivalent to the US, and the work-life balance far superior. No-one works more than a 40-hour week here, as that would mandate overtime payments, a budgetary no-no. Additionally, Public servants get generous holiday, weekend and off-hours shift differentials; something I never got in 25 years of EM practice in the US!

Where Australia saves big money is in the careful integration of care and reduced duplication of efforts. Public Health initiatives like vaccinations are tracked and taken seriously. Outpatient, home health visit Public Health nurses deliver substantial care in non-hospital settings. Pharmaceuticals, both in-hospital and by prescription are heavily concentrated on generics vs brand-names. Hospital Pharmacy formularies are tightly controlled, and closely scrutinized by monthly committees, and cost: benefit data is shared between hospitals and centrally-coordinated. In short, a much more closely coordinated delivery of services, especially on the medication and hospital admission avoidance sides. As well as a much tighter spend on Administrative overhead, which is ~16% of the Private HC budget, but a remarkable 6% in the Public / Medicare system.

http://anmf.org.au/pages/the-facts-on-australias-health-spending

Deficiencies in Australia do exist in the IT (Information Tech) and EMR (Electronic Medical Records) areas. The average Aussie hospital is probably ten years behind the average US hospital, especially in Queensland, where I do most of my work. New South Wales, led by Sydney-centric Tertiary centers and money, has a pretty integrated system State-wide, and Tasmania is coming along. These are expensive, highly complex systems; and Australia is moving cautiously, but steadily ahead. And with only seven States and Territories to integrate, vs fifty in the US, they should have the advantage in terms of cross-border regionalization and integration vs the USA.

Additionally, an often overlooked factor in building a single-payer system, even as a basic safety-net in the US, is the cost of Medical Education. Every politician seems to want doctors to earn less than they do. They won’t. As the longest, most demanding training regimens of any field, physicians will always command and receive a premium for their services, as they should, under any fair system. Capitalism at its finest! Perhaps bankers and politicians should accept pay cuts instead. Humanity will benefit, trust me, I’m a doctor…

But many in the USA seem to expect college/ medical students to work for twelve years to become a Consultant physician, while self-funding most of it through private loans, deferring loan payments, and then be altruistic enough to go into Family Practice or Psychiatry, ideally in a rural or under-served urban area and somehow “work for less.”

US Medical Students and Residents carry the highest average loan burdens of their peers worldwide…for years…I know, I was one. But there has never been a serious public discussion, to my knowledge, of how we as a society, would publicly fund the education of our future doctors and nurses in any such proposed single-payer system. And this doesn’t address all the recent graduates who are carrying massive debt burdens in many cases, that would need to be somehow reimbursed. These costs all need to be considered in the calculus as to approaching a single-payer or hybrid system.

In contrast, Australia and most other western democracies, heavily subsidize their Medical and Nursing students through their years of training, with average tuitions in the $10 K/ year range across disciplines. It’s a well-developed system, many years in the building. Something Americans need to consider as well.

Finally, as the public ages and demand for more high-tech procedures grows dramatically, the costs of healthcare, Public and Private, are projected to increase un-sustainably ahead of all national GDPs. The dirty little secret that no politician wants to discuss is that no one has the answer. Regardless of the approach or system, in a post-industrial, aging world, where western democracy’s GDPs are slowing and demand is rising, along with lifespans; there is no easy answer to containing rising healthcare costs. Australia is no exception, only somewhat better positioned for the inevitable belt-tightening to come. The only certainty to my mind is that endless deficit spending, in lieu of an honest adult conversation regarding what is possible and sustainable, is most certainly the road to ruin.

So, what can America and Americans learn from the Australian Healthcare system in my opinion and experience?

-

A basic, single payer Public system is possible and cost-effective. A hybrid Public/ Private system, similar to Australia’s is even better; reducing public demand and encouraging competition.

-

The USA can afford it; we just need to get our priorities sorted. Do we want more overseas military misadventures, aircraft carriers and jet fighters at umpteen billion apiece, or do we want better, basic healthcare for all citizens? What makes you feel more secure personally, good dependable healthcare coverage for your family, or another aircraft carrier battle group? No contest, IMHO. We need to begin the laborious process of de-militarizing our economy and use the trillions of taxpayer dollars saved to finally benefit the citizens of the USA, full stop.

-

Public Health measures and initiatives give the best bang for the buck on a population basis and should be aggressively expanded and supported.

-

Overall, cost savings can be achieved, but they will be in the areas of limiting Pharmaceutical, Insurance and Administrative overhead. Streamlining systems and containment of costs will become paramount. Front-line personnel and delivery costs may actually increase, though due to the delivery of more actual healthcare to more actual patients; y’know, the whole point of this thing, after all.

-

Public healthcare is about the delivery of reliable, good-quality (not perfect) healthcare to individuals and families. Anything that detracts from this mission, or adds unjustifiable costs, needs to be minimized or eliminated, especially Administrative overhead and importantly, Malpractice and Legal costs.

-

Medical education, in all its facets, is an inescapable cost of building a robust healthcare system. Leveraging existing university networks is critical, and an area where the USA is a world leader.

-

Healthcare IT must be rigorously cost: benefit analyzed with clinician involvement at every step of the process; with adoption and integration operationally regionalized by reduction of political/ state boundary impediments as much as possible; likely via a federal statutory process. But, mandatory IT implementation targets, set by Federal or State decree, however well-intentioned, may represent an expensive diversion of vital clinical funds; and if done poorly results in quantifiable clinician disengagement, increased burnout and loss of efficiency through poor adoption. The goal is practical, streamlined, incremental improvements in efficiency at justifiable cost, always.

-

Efficient and ethical Public healthcare cannot be about making money or showing a return to shareholders. If an alternate Private system wants to try to make a successful business attempt, with an un-subsidized, truly capitalistic, competing model, they should have our complete approval and blessings; but nothing else, beyond member’s premiums and perhaps tax incentives, as in Australia.

-

Detachment of the legal/tort/lawsuit industry from the medical delivery system is long overdue and critical to cost containment and sustainability. While medical liability insurance may represent a relatively minor additional system cost (~ 2%); perversion of clinician behavior, via ingrained cultural changes in practice and test-ordering norms to avoid liability (ie “defensive medicine”) is a massive and almost un-quantifiable reality. Some estimates are as high as 20% of total clinical costs being purely defensive in nature. In the USA, this is roughly equivalent to the entire healthcare budget of France! My experiences in trying to guide and change physician behaviors as an ED Director and hospital Medical Staff President confirms this outrageous waste to me. It simply has to be reduced going forward. Patient’s rights to redress and compensation from legitimate bad medical outcomes, whatever the fault, have been clearly shown to be better-served under mandatory and binding arbitration panels used in other systems. The medical malpractice “lottery” mindset, deeply ingrained in the USA and encroaching now even into Australia, is a perversion we can no longer tolerate or afford, in my view as a practicing EM physician and Medical Director.

Do we want generally safe, efficient healthcare, with its inherent risks of statistically-rare bad outcomes handled predictably, or via a very expensive lottery ticket; with un-affordable medical insurance premiums and reduced trust between providers and patients as consequences? And a lottery ticket with very low odds of one ever hitting the jackpot at that? Ultimately, it’s our choice to make, and implement, as a society.

The future for all advanced countries will involve making informed, wise choices regarding costs: benefits, limitations of care, and attaining consensus on best outcomes for populations vs individuals. There will be hard choices to be made regarding withholding of heroic, end-of-life care. No current system can survive the demographic Tsunami wave now bearing down on us all, without radically re-envisioning healthcare delivery. Further deficit spending to avoid these uncomfortable, yet vital, discussions is unethical, counter-productive and ultimately doomed to fail, with disastrous societal results. After all, once we are essentially forced into spending reductions as a terminally insolvent society, who’s healthcare needs will take priority; the vast bulk of fading baby boomers, or the still productive millennials and their children? The answer is obvious to me.

In sum, Australia’s healthcare system, while hardly perfect, is better than America’s. It just is. As a dual citizen and practicing physician I am unequivocal on this point. Sorry to break the harsh news…

Though I do tell my Aussie colleagues, “I love Australia’s healthcare system, you should be very proud of it. I’m just not sure you are going to be able to afford it going forward.” Especially given the Aussie public’s increasingly unrealistic demands and expectations of it, and the encroaching, parasitic malpractice environment, modeled as it is, on the good old US of A.

In closing, to quote the ever insightful Winston Churchill…”The Americans can always be counted on to do the right thing, after they’ve exhausted all other options…”

Are we Americans finally exhausted enough to learn from other’s experiences and try another option? They already do exist, after all…